Anyone who knows about my photography, knows I nearly always shoot in Camera RAW. Why? Better control over the finished product. Old school film photographers often went to great lengths with special lens filters, reflectors and gels to get detail in the shadows without blowing away light areas in a picture. Then there were chemical baths and other darkroom tricks needed to get the desired results.

While I admit I could stand to learn more about using those tools, unless you are doing specialized work much is rendered unnecessary when taking full advantage of the digital toolbox offered with Camera RAW, which up until recently was only available with DSLRs. Now, some of the higher end smartphones offer RAW capture.

The problem with JPEGs is a lot of data captured by the sensor is thrown out by the low-powered computer in the camera based on algorithms and guess-work operator adjustments on camera.

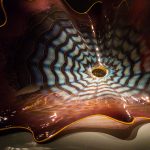

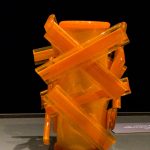

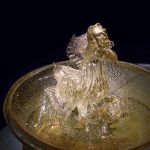

I decided to use an exhibit of Dale Chihuly’s Venetian Glass at the Reading Museum as a test of the capabilities of RAW capture on an LG-G5 Android phone. (Most manufacturers now have one or two top-end models that offer a manual mode with RAW-capture capability.) The Chihulys are a bit of a challenge because reflections on facets of the glass work tend to result in blown-out detail. I was pleased with the results, which required only minimal tweaking when developed using Adobe Camera RAW (ACR).

The pictures here were all shot in the phone’s manual dual-capture mode and are derived from the DNG captures, rather than from the JPEG clones. I developed them off-phone using ACR in Photoshop CC (2016).

Although there was noticeable loss of detail and clarity in the JPEGs, most of them were acceptable for posting on social media with little or no adjustment. They were also fine for making small prints. Because the zoom on cell phones is exclusively digital, the JPEGs have the advantage, from the point of view of instant use, of holding the zoomed crop. The RAW (DNG [Adobe’s Digital NeGative format]) files produced by the same shot were the full uncropped image.

In most cases, I used a low ISO and relatively fast shutter speed to limit noise and to maintain a nice dark black background.

Detail can be recovered from clipped areas (especially in bright areas, but also in shadow) using ACR. The luminosity tool in ACR enables developing crisp, more vibrant colors in the pictures without over-saturation. In picture “VS987-8” I used an old “High Pass” Photoshop trick to enhance the structure of the vessel, which appeared a little flat in the original. The lens on the G5 is rated at f-1.8, making it good for low light situations. (The iPhone 7 has a considerably slower f-2.2 lens). Nevertheless, the aperture on these lenses is not adjustable like on a DSLR. While an 1.8 lens on a DSLR would create superior dimensionality, the short distance between the lens and the sensor and the small sensor size puts limits. The only way to control depth of field is by moving closer to the subject to blur the background. In a museum setting that isn’t always possible.

A Note about versions of ACR: Although Photoshop Elements (a tool for beginners and occasional photographers) comes with a stripped down version of ACR, it lacks a number of tools I consider essential (the Adjustment Brush is at the top of my list of must-haves), which are only available with the CC version or in Adobe Lightroom.

I’ve also found Google’s Snapseed App is a very good tool for developing both JPEGs or DNG files directly on a tablet or smartphone. But you are still dealing with the limitations of the processor and small screen on a phone compared with the higher powered processor and larger monitors on a desktop or laptop computer.