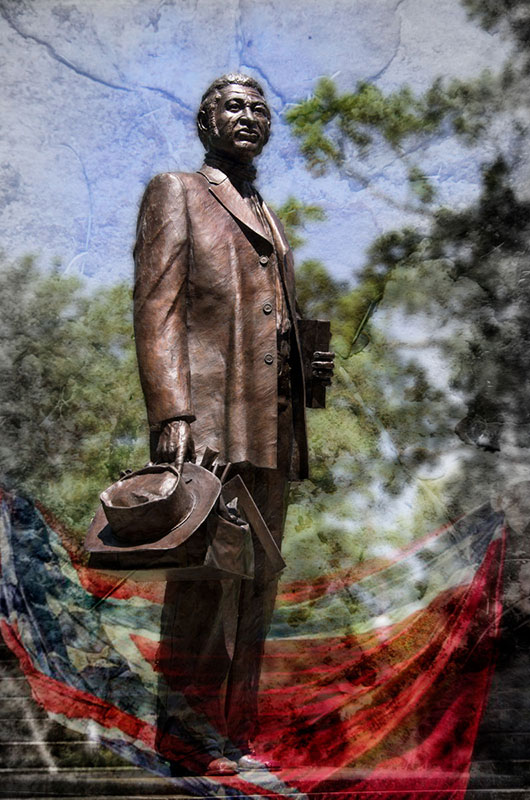

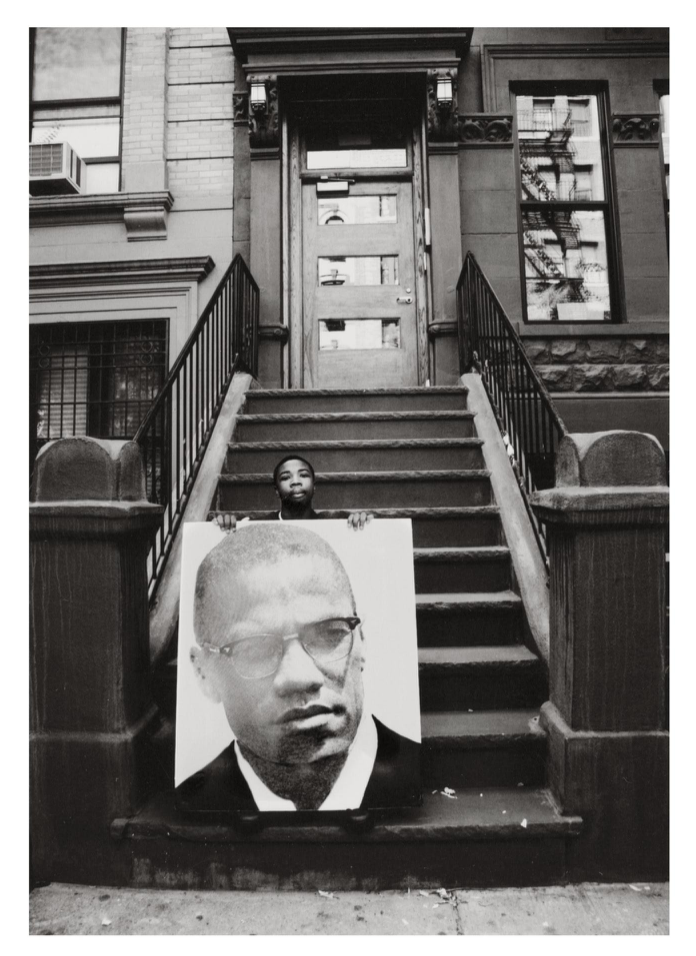

A Composite Photo by Jay Ressler from the upcoming exhibit “Doubletake East” by Martha & Jay Ressler in Reading, PA, at Judy’s on Cherry .

Sights and Insights

A Composite Photo by Jay Ressler from the upcoming exhibit “Doubletake East” by Martha & Jay Ressler in Reading, PA, at Judy’s on Cherry .

Denmark Vessey, a well-educated and dignified former slave helped found “Mother” Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church in Charleston, SC. He planned a slave rebellion in 1822 and was hanged along with more than 30 others. In 2014 a statue honoring him was erected in Charleston, S.C. park. A year later the Confederate Flag, a symbol of racist terror, was finally removed from the State House. Since then removal of statues glorifying the slave-holders’ rebellion from public spaces is gaining momentum.

Considering the murder of Heather Hayer in Charlottesville, VA, by a racist thug while cops whistled Dixie, the struggle to recognize that Black Lives Matter assumes even greater urgency.

This piece is being exhibited at the Yocum Institute for Arts Education in an exhibit entitled “Make Art Great Again: Left, Right and In-Between.” September 7 to November 8, 2017.

Opening Reception September 7, 5:00 PM • 1100 Belmont Avenue, Wyomissing, PA 19610.

This composite photograph is a new addition to my “Seven Deadly Sins” series and will be appear in my upcoming show at Clay on Main in Oley, PA. The opening is January 8, 2017, 4-6 PM.

To read more about this piece go here. To preview the whole series with commentary go here.

(The composite was created by combining and digitally blending still shots I made of video from Mariela Castro’s March: Cuba’s LGBT Revolution and The Normal Heart.)

It’s not uncommon for birds of prey to get hit by cars. Several years ago while walking around the East Liberty section of Pittsburgh I found the disembodied foot and leg of a Peregrine Falcon on the street. After taking it back to the studio and photographing it, I began working on this composite photo. I only now finished it after uncovering the partially completed project in my files.

While harking back to Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds, the piece addresses the reckless destruction of the natural world by the modern capitalist social system.

In Review

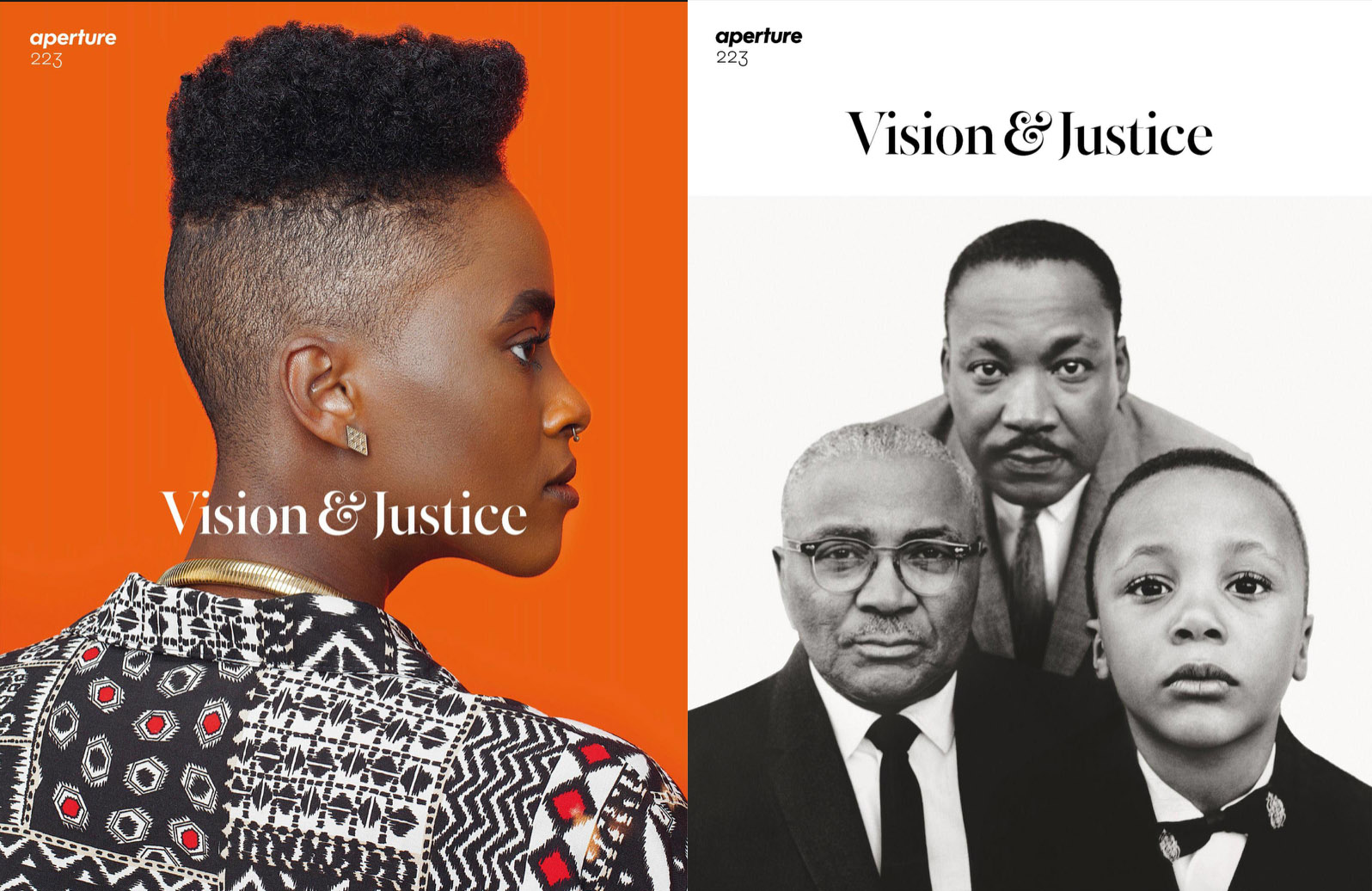

In keeping with a part of the mission of this blog [“Sights and Insights”] I’m devoting this installment to a brief review of the Summer 2016 issue of Aperture Magazine [No. 223], entitled “Vision and Justice.” [The print edition is temporarily sold out, but reprints will be available next month. The digital version can be purchased here.]

Aperture is a quarterly journal for photographic artists and serious followers of the medium founded in 1952 by editor Minor White along with Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Barbara Morgan, and curators Nancy and Beaumont Newhall. This is the first issue to devote itself exclusively to the struggle of African-Americans for equality and well worth the time to savor and study.

The murders of the Mother Emmanuel 9 in Charleston, the police murders of Freddie Grey and Eric Garner (and so many more since), and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement provide the immediate impetus for publication of this special number. The controversy concerning the dearth of Black nominees and award-winners at the Academy Awards ceremony in February 2016 also informs the issue. But editor Sarah Lewis, who teaches the history of art and architecture and African-American Studies at Harvard, is careful to employ a much broader brush in assembling this collection of photographs and essays.

Lewis writes: “Published in the last year of the Obama presidency, this issue marks a time of unparalleled visibility for an African American family on the world stage. Yet this era must also be defined by the emergence of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the stagnated wages of working-class citizens, and growing impatience with mass incarceration.”

Her second sentence is more to the point. Resistance by workers and young people, especially among African Americans, to the grinding depression conditions and deepening assaults on democratic rights are emerging in ever more insistent ways on the political stage.

“It is the artist who knows what images need to be seen to affect change and alter history, to shine a spotlight in ways that will result in sustained attention,” Lewis asserts.

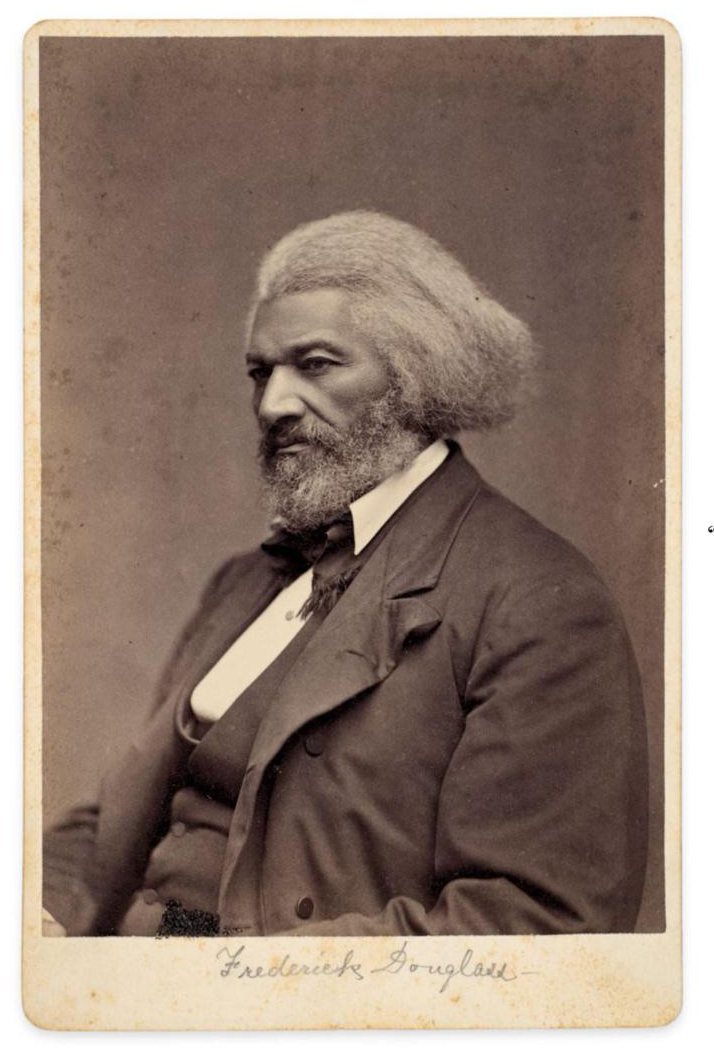

“This issue,” she continues, “takes its conceptual inspiration from the abolitionist and great nineteenth-century thinker Frederick Douglass, who understood this long ago. In a Civil War speech, ‘Pictures and Progress,’ Douglass spoke about the transformative power of pictures to affect a new vision for the nation.”

Douglass was the most photographed American in the nineteenth century and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s piece on Douglass probes the importance of photography as an instrument of struggle for emancipation and liberation.

I refer the reader to Lewis’ full introduction, which summarizes her perspective better than I can, here.

Other portions of the issue are still available on the Aperture website without a subscription: including “Black Lives, Silver Screen: Ava DuVernay and Bradford Young in Conversation” along with a powerful interview: “Love Visual: A Conversation with Haile Gerima” By Sarah Lewis and Dagmawi Woubshet. DuVernay is the director of Selma and the first African-American director to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture; Young is an award-winning cinematographer who worked on Selma. Haile Gerima directed the 1982 film Ashes & Embers about a disillusioned Black Vietnam veteran.

Both of these latter pieces highlight the difficult challenges and limitations black filmmakers confront in using motion pictures as a vehicle for promoting the struggle for liberation given the fundamentally white supremacist nature of the industry, both in its historic inception and in its current reality.

“It’s not like jazz or hip-hop—art forms that started as expressions of dissonance and resistance. Filmmaking isn’t part of our organic narrative as black people in America. We’re asking people who were very much interested in making sure film communicated white supremacist values, like the founding fathers of the film experience—D. W. Griffith, Thomas Edison, these people who were very interested in white supremacy—we’re asking the sort of grandchildren of those people to allow us into the filmmaking experience with a whole counterpoint to why they started it,” says Young in his conversation with DuVernay.

I picked six photos I found particularly striking to recommend the issue.

Deana Lawson’s photograph (shown above) of Gracie Broome, grandmother of Reverend Clementa Pinckney, one of the Mother Emmanuel 9 assassinated in 2015, holding a portrait of Pinckney as a young man is among the most stirring in the issue and a fitting end piece for the collection.

Ethiopian-born Awol Erizku’s reimagining of Vermeer’s girl with a pearl earring is part of a series that forces us to reexamine the masterpieces’ of Western art through the lens of the black diaspora.

In this brief review its impossible to mention all the treasures in this issue. But I do want take note of the inclusion of several pictures by celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz. The most distinctive of those included (and in my opinion one of Leibovitz’ best photos ever, if that judgment is possible) is a portrait of Serena Williams spread over half the frame with her arms flung apart with her hair billowing behind. A crimson dress sculpts her muscular body capturing not just William’s beauty but her heart, power, and will to excel.

Among the most interesting collection of photographs are a series of Black and White portraits from Dawoud Bey’s Birmingham Project, in which Bey has paired Birmingham youth and adults. The youths are the same ages as the victims of the bombing by Klansmen at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963. The pairings pose poignant “what if” questions.

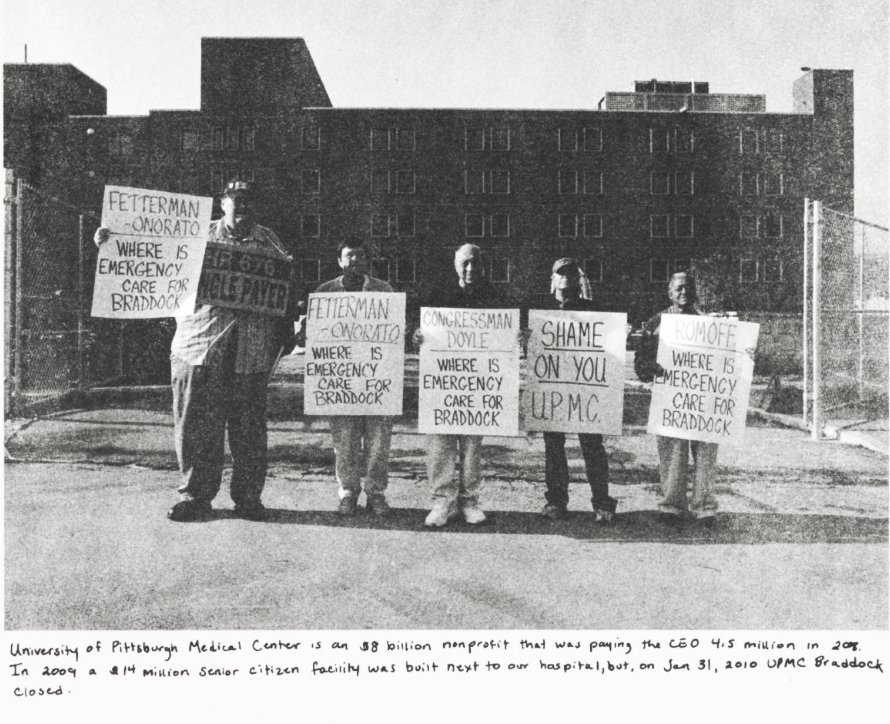

In her pictures of her native Braddock, PA, LaToya Ruby Frazier captures the devastated and ruined landscape of a once-booming industrial town sitting in the shadow of the USX’ still-booming giant Edgar Thompson mill, which now employs few townspeople.

In contrast to the pictures of rubble, twisted steel, the sick and utterly impoverished in Frazier’s photos is the dignity captured in Jamel Shabazz’s street portraiture of subjects framed by regalia often of their own creation. “Black people dignified, noble, shoulders back but with a slight lean to the side,” says Khalil Gibran Muhammad in his essay on Shabazz.

Two portraits of the greatest American* revolutionary of the Twentieth Century, Malcolm X, appear in the issue, both look like they are from the period before his return from the Hajj and his break with Elijah Mohammad. Still, Shabazz’s 2008 picture of an unnamed young man sitting on a Harem stoop holding a giant picture of Malcolm makes a statement about his enduring example and legacy. The second is a wonderful side shot of Malcolm wearing a fedora pulled forward, with his hand on the back of his neck so that his forearm covers his chin. It accompanies Hank Willis Thomas’ “List of Favorite Anythings,” in which he lists the Autobiography of Malcolm X. “What I love most about it,” he says, “is that in it, we watch Malcolm redefine himself completely, continually willing to evolve his ideas regardless of the risk. The most revolutionary thing a person can do is to be open to change.”

*I use the word “American,” as opposed to “African-American,” purposely. Malcolm was unquestionably African-American and a decidedly militant proponent of the cause of African-American liberation but in his conduct was an example whose importance goes far beyond the Black community. He contended the American reality is a nightmare, not a dream emphasizing “I’m not an American. I’m one of 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism.” In 1987 Jack Barnes, who interviewed Malcolm for the Young Socialist magazine in 1965, asserted “Malcolm X was a revolutionary leader of the working class of the United States.” See Malcolm X, Black Liberation & The Road to Workers Power, by Jack Barnes. In that sense, he was an American, albeit one who started with the world and looked toward a revolutionary transformation of America in the interests of the oppressed.